Daniel Dewar & Grégory Gicquel

Oiled oak bodies and cinnabar stitches

Works

Installation Views

Press Release

Jan Kaps is pleased to present Daniel Dewar and Grégory Gicquel’s third exhibition at the gallery, Oiled Oak Bodies and Cinnabar Stitches, comprising newly produced works including five benches and one cabinet in carved oakwood, and an altogether new suite of embroidered and quilted wall hangings.

The British-French duo continue their ongoing foray into humankind’s relationship to labour and production and the historical separation of autonomous work of art from utilitarian furniture, all the while revealing an unfaltering curiosity for the porosities between animate and inanimate, between nature and culture, between that which was, is, and that which is perhaps yet to come.

A first suite of five carved oak benches sit aligned, overridden with oversized snails tucked into their spiralled shells. Each bench is topped by an intricate cushion decorated with mechanically stitched creatures. In an embroidered rendition of an entomologist’s coloured illustrations, the needle pierces fabric and sews thread rather than pinning down real-life coleoptera. As is often the case in Dewar and Gicquel’s practice, a precise adequacy is found between subject matter and craft technique: the machine-embroidered stitches flicker just as the insects' wings and flower petals would flutter upon a breeze.

An imposing oak cabinet featuring functional hinged doors is not decorated so much as the embodied images emerge out of the wood. Below a giant resting Flanders rabbit dangle multiple toes. Placed in this strange vertical position and sometimes grouped by more than five at a time, the digits appear as boneless fleshy protrusions, udders, or layered feathers. The work encapsulates an analogy between the rabbit’s fur, the downfacing toes, and the grain of the wood. Just like stroking an animal’s pelt, the wood must be carefully carved following the grain to reach the path of least resistance, and of most respect for the material (or being). Human authority, albeit represented by the least prestigious part of our bodies, is quashed as the artists allow the wood to dictate the position of the limbs depicted.

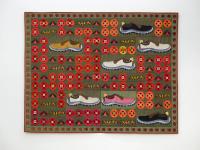

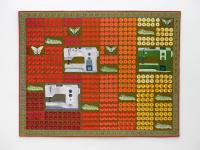

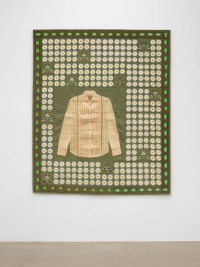

Four quilts hang in the space, each an assembly of individual green linen squares and rectangles, embroidered by a computer-assisted machine. These new pieces capture and complexify many of Dewar and Gicquel’s processes and concerns: a contrast is made between the organic motifs and the very mechanical technique used, with pixel-like glitches to be found at the joints of each embroidered section as age-old technique is hurtled against our recent tendency to read everything as a screen. The supposed division of artistic work and manual labour is entertained by the presence of a safety shoe, and heightened by the tautology or “mise en abyme” of the sewing machine. Cinnabar caterpillars are placed aside moths, and swallowtail caterpillars next to butterflies, hinting at ideas of transformation and becoming: what we might call Nature’s “work” in a state of constant flux. This impression of movement continues by means of the repetition and placement of motifs as we are led to think of proto-animation and early computing: musical scores, punched jacquard cards, or praxinoscopes.

“Milk, mud, puddles and earthy apples, water, sap, blood, animals and plants of Europe.” (1) Animal, plant, mineral, human. In 1609, the German alchemist and professor of medicine Oswald Croll noted the walnut to be effective in healing “wounds of the pericranium” as it looks “exactly like the brain in appearance.” (2) Early Modern occidental science—as well as many non-western medicinal practices—used visual analogies to understand the properties of plants, and the boundaries between categories were not quite so clearly delineated as we may generally consider them today. Daniel Dewar and Grégory Gicquel perpetuate this aristotelian conception in order to question the value of human knowledge and decentralise or de-hierarchise our position, rethinking our relationship to the natural world and the impact our toils and troubles may have upon it.

1 Daniel Dewar & Grégory Gicquel, Sculptures in the round, Secession, Vienna, 2021, p. 3. 2 Oswald Croll, Traité des signatures, 1609, in Foucault, Order of Things, 1966, Routledge English edition, 1989, p. 31.