Works

Installation Views

Press Release

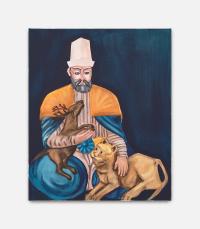

Das Universum ist die sichtbare Gestalt Gottes Das wichtigste Buch zum Lesen ist der Mensch -Hacı Bektaş Veli

Jan Kaps is pleased to present “Speaking in Tongues,” a special new series of works by Cologne-based artist, Melike Kara.

Native language, or the mother tongue, is what defines us. Language structures our understanding even as it creates ties to family, friends and strangers. But, what if it is dangerous to speak and write your native tongue? Melike Kara, born to a Kurdish Alevi family targeted for their culture, uses this return to the Rhineland to investigate her work’s powerfully ambiguous experience with a mother tongue that feels like home, but is no longer spoken or understood.

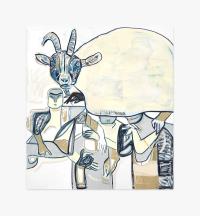

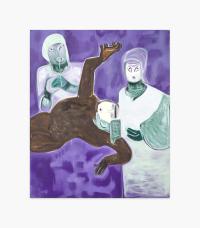

Kara has spoken of her paintings' uniquely inter-locking groups of unidentifiable, genderless individualities as articulating identity without recourse to a surface. Each group creates identity for all its individuals. Here, we get a new sense of the depth of history and culture below the abstracted surface.

In the Jülicher Strasse gallery, the paintings' individuals are shown gazing towards exactly what their surface abstractions have never meant to erase. As if from out of the collective unconsciousnesses of her paintings, Kara brings to the surface the remote huts found in Northeastern Turkey, where her grandmother used to organize ritual sacrifices. For political reasons, these ancient traditions are extinct today. Kara's traditional, Kurdish clay sculpture of an empty site of culture sets the forced absence at play, a screen on which one might project a real memory of a golden age.

Apples, metamorphosed by cloves into golden gifts, embody the imaginary Shangri-La as a counterpoint to “Emine,” Kara's ficto-documentary portrait projected in the second room, of her grandmother's world as it disappears and reappears in the tides of history and alzheimer's disease.

In the Vosberg Space's installation, “fal (a) bakmak,” she draws on the fortune telling tradition which crosses many of the cultural boundaries breaking apart Kurdistan. The number of individual cups, each borrowed from a different, now unremembered and uninterpretable future, join with Kara to perform and articulate the sutures between notions of identity and culture. Occupying the gallery as a glossolalia, they describe the communities discoverable by the sharing of such fragments.

Looking out upon the city, as well as into the gallery, are a number of forms and faces with identity as perfectly indescribable to the outside as they are shared in defining on the inside. In these paintings, vivid, ancient motifs come into sudden focus; animals join masked humans as if to look at us with recognizable aftertaste. But of these paintings, one is in an altogether different pictorial language: a portrait of a recognizable historical human being. Merging from a color field, looking happier than he has in years, Hacı Bektaş Veli, the thirteenth century scholar, scientist, poet -- the founder of the rational Dervishes himself—gently, but deeply, enlarges this intimate community of gazes.