Works

Installation Views

Press Release

Jean-Marie Appriou, Seabed

O Lurçat, communist weaver from the Massif Central, may this rough slab originating from before the ages meet a brilliant future! O Lurçat, your roosters, your foliage, your arabesques, your standing figures, your Chant du Monde! O Lurçat, no less than two large wall tapestries were needed to set the Youth ball rolling! Consortium Museum, Dijon. The whippersnappers have become these new masters, experts in virtuosity, in express deliveries, in assumed power, in career plans––in those quarries from which cubes, metamorphic limestone plates with salient veins are extracted, with their iridescent shimmers...

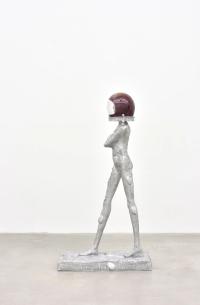

There is a new small population of Y.T.J. (younger than the Jesus!) that came center stage, paying tribute to craftsmanship, to the labors of the foundry, to modeling, to etching, to clay and enamel. This is where Jean-Marie Appriou stands.

O Lurçat, so similar to Léger the builder: an arrogant introduction sets the bar as high as a gold medal, and then unfolds the cohort of the 26 pieces in the exhibition (23 of which are new artworks unveiled for the occasion), adorned anew with micro-narratives and recurring characters: here is the Astronaut, here is the Beekeeper...

Are they coming straight out of Rudolph Dirks’s Katzenjammer Kids? The Captain and the Astronaut. King Bongo: he is the artist, the extremely smart and nimble island aboriginal who can dress up as an animal or as a plant. He knows the language of animals, and escapes on his domesticated stork. I am the Astronomer, long white beard and top hat...

All of this to say that everything here comes from a long way away.

Finistère Nord, peasants turned proletarians, unionized foundry workers at the Brest shipyards; Art Deco and its academic, modernist statues that don’t meet the eyes anymore, too high up as they are clinging to our city hall belfries or to suburban concrete churches: these are an accelerator for today!

O Sarrabezolles, you who carved directly on setting concrete, perched on blasted, rickety scaffolds, forty meters above the ground, your laborers arranged like a surrounding choir! In 1926 in Villemomble, he experimented for the first time with this daring technique that doesn’t permit any post editing, carving more than twenty sculptures over sixty-three days for the Saint-Louis church belfry.

O Lurçat: an ode to labor among electric rapscallions (let’s recall the Manifeste électrique aux paupières de jupes [Electric Manifesto with Skirt Eyelids] signed by Michel Bulteau and Matthieu Messagier... in 1971), handily experienced with sculpture’s drills. O, Alfred-Auguste Janniot, here I am taking over: at the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, for Jacques-Émile Ruhlmann’s Hôtel du Collectionneur, he made a sculpture representing a group of three muses, paying homage to Jean Goujon; at the Curie intersection in Paris, he created the pediment for a double building by Joseph Marrast (À La Gloire de la Seine, 1932); at the Palais de la Porte Dorée in Paris, the shamefulness of colonization is rendered in magnificent bas-reliefs (Paris Colonial Exhibition, 1931); and then there is the Palais de Tokyo (1937 World’s Fair), and all the other Houses of the Republic commissioned for the glory of Worlds’ Fairs.

The foundry, the deliciously old-fashioned or invariant studio, ever since the eons of cave painting.

O Lurçat, sweet Stalinist with your loaded wool: a new example for our youth escaping from the art factories, confronting the ... organic market on Saint-Germain-des-Prés on Sundays.

Binaries are in our DNA, whether we are talking about jeans, which are sometimes skinny, sometimes bell-bottomed; or about waiting rooms in 2000s Chinese train stations, that ranged from softness (the comfortable moleskin bench seats in first class) to stiffness (the wooden benches for the labor class); as for sculpture this dual scansion is not lacking: is it smooth, as with antique or Maillol sculptures, or is it the abstract, rough type, as with Reg Butler or Etienne-Martin? ... the kind of sculpture that has you itching to turn back to figures and to narratives. Appriou has grabbed the green side of the Scotch Brite scrubber, the one that scratches wandering hands going astray on touch, on contact. The type of sculpture that has you itching for something, as with Picasso’s bewitching, engraved concrete sculptures––he was sought out by Carl Nesjar for commissions in Norway; together they perfected the technique.

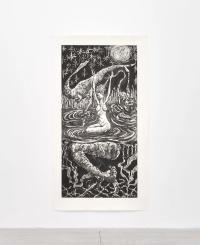

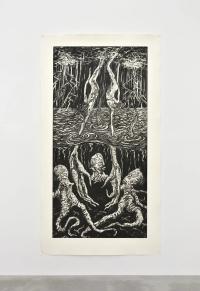

Art is still something to take a stand on, confronted with an inert matter, or on the contrary with a matter traversed with land movements, a manual practice––which is not a working-class glorification of labor––connected to all these critters, particles and brain nodes. Happy culture. The Beekeper, the Astronaut with his blown glass helmet screwed over his head, the dinosaurs, the birds with their elongated beaks searching for worms in the mud ... Jonas and Ophelia.

Art needs new geographies, to get accustomed to immemorial gestures. These places are harsh grounds for the Resistance, and for French May 1968 dropouts to let loose and raise goats. There, you can find potters wheeling clay, enamellers and foundry masters. From the Vercors, once the Massif Central has been left behind for the Alps, remains the harshness of the windy high plateaus with their bloodstained legends and massacres. The Cévennes mountain ridges, like parallel bars to narrow peaks, have for advantage to get some sun, and the same arrogance as mountain people who have gotten into the habit of looking down with hawk eyes on the valley down below, that has maybe remained Roman Catholic.

Appriou’s art has a matte aspect, gray as aluminum, terse and thorny. Today, it expands toward prior forays into ceramics, which befits celadon and ultramarine glazes––bas-relief––with glass blown inside a mold, with copper engravings, with cast bronze––also bas-relief––which also befits a moonlike or swamp-like verdigris patina... Appriou’s art has you itching for another look––to have it founded and anchored if needed––at the forgotten animations of cities’ downtown bas-reliefs, at the floral ornamentations, at the useful and pompous symbolisms of bridges thrown over a main river, at funerary sculptures inside cemeteries, at tombstones with their famed recumbent effigies, whose bulge at the groin is worn out after having been polished by so many devout hands! Appriou’s art incites desire, has you itching for something else. To have another look, to see more, to see again previous sculptures and to display them on an oriented axis, to find kinships or cousinhood for them, to see them flirting with old and new, with his peers’ contemporaneity––whether we should be compelled to do so is not certain. Appriou enjoys tackling everything, for anyone who will kindly bring an offer in his purview: a public commission for the Rennes train station, a bid for another decorative commission for a prestigious elite French school... With seriousness and brio, the artist takes up a commission for a place that is for the public, for open air, for a dense city that lampoons the art of public bidding, arguing about the frequent inanity of such situations and commissions, as with the recent unveiling of a group of three monumental sculptures for Central Park South in New York initiated by the Public Art Fund. Three cast aluminum horses are placed directly on the ground, facing the military gilded equestrian statue of General William Tecumseh Sherman, a tangent to the tourist horse-drawn carriages. Nothing can stop the young guard.

––Franck Gautherot