Akosua Viktoria Adu-Sanyah

Hypoxia

Works

Installation Views

Press Release

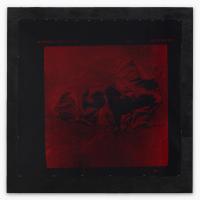

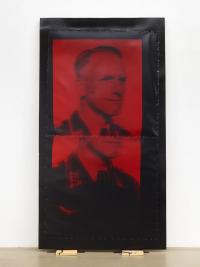

Can photographs forget? Can they suddenly cease to depict the suffering they once documented, no longer represent it? Or are we the ones who choose to stop remembering? The horrors of the past fade—just like the images that have preserved them over the years. The photographs and installations of Akosua Viktoria Adu-Sanyah are both records of their time and of their own creation. They capture something while simultaneously embodying a process of deconstruction, decay, and dissolution. For her exhibition Corner Dry Lungs at MMK Zollamt in Frankfurt in late 2024, she unrolled large sheets of analog photographic paper in a room that was not darkened. The paper was immediately exposed and changed color. Subsequently, she treated it with developer, rinsed it with water, crumpled it, stuffed it into large black bags, took it out, soaked it, stuffed it back—repeating the process multiple times—before stapling the large sheets onto black frames. These “lungs” gradually filled the exhibition space, leaning against the walls, dripping, living, mourning—an expression of a loss that could not even grasp itself. This raises a central question that lies at the heart of photography and has gained urgency again in recent years. In her 2003 essay Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag questions how the depiction of war, violence, and suffering in photographs shapes our perception of conflicts and our compassion. The question—then as now—is to understand whether and how these images foster empathy and humanitarian engagement or whether they desensitize viewers. Do we merely observe—or have we always been a part of it? This idea is closely linked to Adu-Sanyah’s work. In the exhibition Hypoxia at Jan Kaps, alongside the “lungs” that were adapted or amputated to fit the space, three additional photographic works are displayed. They show: a dead tree, a photograph of fabric remnants covering chains in a former torture cellar for enslaved women in the Portuguese-built Fort São Jorge da Mina on the coast of present-day Ghana, and a portrait from the 1930s showing the artist’s great-grandfather, Wilhelm Schlüter, in his uniform as a corporal in the German Luftwaffe. Three images created in the immediate present yet representing three very different temporalities. Three images that directly or indirectly negotiate suffering and evil. These are analog prints, visually rather dark—black and white, or more precisely, black and red. The artist omits color filters, and the remaining white light produces this effect. Particularly the tree and the photograph of fabric remnants and chains are so reduced in color that their texture becomes a kind of optical relief. The examination and negotiation of evil was already a subject of Dante Alighieri, who in his Inferno not only described hell but also reflected on morality, justice, and the nature of evil. Adu-Sanyah also addresses another crucial element that is indispensable in this discourse: powerlessness. The exhibition title Hypoxia serves as an allegory for precisely this—a lack of oxygen in living beings, the resulting breathlessness and helplessness. Likewise, the “dry lungs,” as the artist describes them for her exhibition at MMK Frankfurt, symbolize precisely this sense of oppression and lack of agency. Moreover, many bombs have a similar effect: during detonation, they extract oxygen from their surroundings, and the resulting vacuum causes the air in the lungs to expand, often leading to fatal injuries. The tree as a symbol of strength—yet here, a lifeless shell. The fabric remnants as silent witnesses to senseless violence and oppression. The photograph of a family member whose mere appearance and clothing are so charged with evil that seeing any good in him becomes nearly impossible. Akosua Viktoria Adu-Sanyah’s work is an impressive exploration of the individual’s position in relation to the suffering of others. Neither she nor her work assumes the role of a victim; rather, they embody that of a rebel—someone who resists, processes memory, relentlessly continues, and gradually comes to understand their role. It is a work in defiance of forgetting. Fabian Schöneich, 2025